Regimental

History: 1863 (continued)

fter a day's rest, the 28th Massachusetts

rushed with the rest of its brigade and corps into Pennsylvania, where

the beleaguered leading elements of the Union army had become engaged

just north of Gettysburg. But the 2nd Corps arrived too late to be of

any help in the savage fighting that took place on July 1.

fter a day's rest, the 28th Massachusetts

rushed with the rest of its brigade and corps into Pennsylvania, where

the beleaguered leading elements of the Union army had become engaged

just north of Gettysburg. But the 2nd Corps arrived too late to be of

any help in the savage fighting that took place on July 1.

On

the morning of July 2, the 28th Massachusetts was positioned near the

center of the Union line along the crest of Cemetery Ridge, waiting in

reserve well into the afternoon. Then, Maj. Gen. Hancock ordered

Caldwell's 1st Division, which included the Irish Brigade, to form up

and reinforce the faltering left end of the federal line. Before the

advance, Father William Corby, the brigade's chaplain, stood on a rock

and pronounced general absolution to the Irishmen kneeling around him.

On

the morning of July 2, the 28th Massachusetts was positioned near the

center of the Union line along the crest of Cemetery Ridge, waiting in

reserve well into the afternoon. Then, Maj. Gen. Hancock ordered

Caldwell's 1st Division, which included the Irish Brigade, to form up

and reinforce the faltering left end of the federal line. Before the

advance, Father William Corby, the brigade's chaplain, stood on a rock

and pronounced general absolution to the Irishmen kneeling around him.

Just moments later, the 28th Massachusetts

and the rest of the Irish Brigade charged first into the Wheatfield,

and then into a forested area beyond it known as the Stony Knoll. The

rapid advance took the Confederates by surprise, with the Irish taking

a large number of prisoners. Those rebels not captured fled into the

woods and to the Rose Farm beyond. This was an important attack because

it helped repel a Confederate assault that was poised to overwhelm the

entire Union position. Before its men could celebrate a hard-won

victory, however, the Irish Brigade was flanked on the right by

Confederate reinforcements who had broken through in the Peach Orchard.

Facing

imminent capture, Col. Byrnes picked up the regimental colors and

coolly led his men back through the blood-soaked Wheatfield, all the

while ordering them to fire volleys at the rebels in pursuit. During

the charge and subsequent repulse, the 28th Massachusetts lost 107 men

- nearly half of the 224 it had brought into the battle. Many were

wounded and left on the field to be captured during the retreat.

Facing

imminent capture, Col. Byrnes picked up the regimental colors and

coolly led his men back through the blood-soaked Wheatfield, all the

while ordering them to fire volleys at the rebels in pursuit. During

the charge and subsequent repulse, the 28th Massachusetts lost 107 men

- nearly half of the 224 it had brought into the battle. Many were

wounded and left on the field to be captured during the retreat.

What remained of the Irish Brigade was

ordered back to Cemetery Ridge for the night. Upon returning to their

original position, the men of the 28th Massachusetts went to work

building rough breastworks of rocks and fence rails. There they

remained on the morning of July 3, trading occasional shots with rebel

pickets while awaiting Gen. Lee's next move.

Suddenly, the ominous stillness was broken

with a barrage of Confederate artillery fire on the federal positions

along Cemetery Ridge. Although the air was filled with projectiles,

most of them flew well over the heads of the Irish, landing on the

higher points of the ridge behind them. A few men in the 28th

Massachusetts suffered minor wounds. When the cannonade stopped, the

Confederate advance that came to be known as Pickett's Charge began.

The rebel objective was the center of the 2nd Corps position, more than

a mile to the right of the Irish Brigade. In spite of the distance, the

men of the 28th managed to fire a number of long-range volleys at the

passing rebel troops and brought in prisoners who surrendered near

their lines.

Four days after the repulse of Pickett's

Charge and two after the Confederates withdrew from Gettysburg, the

Irish Brigade remained in position on Cemetery Ridge, seeking to locate

and bury its dead. While the battle had ended in significant Union

victory, Meade opted against immediate pursuit of Lee's retreating

rebel army to give his own forces time to recuperate, but would soon

renew the offensive toward Richmond.

Four days after the repulse of Pickett's

Charge and two after the Confederates withdrew from Gettysburg, the

Irish Brigade remained in position on Cemetery Ridge, seeking to locate

and bury its dead. While the battle had ended in significant Union

victory, Meade opted against immediate pursuit of Lee's retreating

rebel army to give his own forces time to recuperate, but would soon

renew the offensive toward Richmond.

The 28th Massachusetts left Gettysburg on

July 7, marching through Taneytown and Frederick, Maryland, over the

next two days, crossing South Mountain at Crampton's Gap on July 10,

and reached Falling Waters opposite Harper's Ferry on July 15. From

there, the Irish crossed the Potomac into Virginia on July 18, and

marched south through Snicker's Gap, Bloomfield and Ashby's Gap,

arriving at Manassas Gap by July 24. From there, there was another week

of exhausting marches across the Virginia countryside. The regiment

finally went into camp at Morrisville on July 31 and would remain there

for an entire month to rest and refit. The 28th marched on the final

day of August to U.S. Ford in support of a cavalry action, but returned

to camp less than a week later.

On September 10, the much-depleted ranks of

the regiment were partially restored to more than 300 men with the

addition of 175 draftees from Massachusetts. Some of these men would

prove to be good soldiers, but many were reluctant fighters and a

number were completely opposed to the war. Desertions had always

plagued the regiment, but now they would multiply with the prospect of

long forced marches and frequent skirmishes ahead.

The 28th Massachusetts left camp again two

days later, marching via Culpepper to Rapidan Station by September 17.

There, the Irish were assigned picket duty, and remained on the lines

until October 6, when they moved back toward Culpepper. On October 12

at Auburn Hill, enemy shelling forced the regiment to retreat. The 28th

skirmished with its Confederate pursuers along the route, suffering six

casualties, and Brig. Gen. John Caldwell reported that "the men showed

but little confusion, and kept their ranks while moving around the

hill, the conscripts moving nearly as steady as old soldiers."

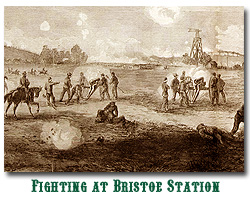

Acting as the Union army's rear guard,

the 28th Massachusetts continued through Catlett's Station, and

arriving back at Bristoe Station joined the main body of the 2nd Corps

along a railroad embankment, once again enduring heavy artillery fire.

After the bombardment, Gen. Lee ordered several divisions forward to

attack the Union line, but they were easily repulsed. The rebels

suffered heavy casualties; the 28th none.

Acting as the Union army's rear guard,

the 28th Massachusetts continued through Catlett's Station, and

arriving back at Bristoe Station joined the main body of the 2nd Corps

along a railroad embankment, once again enduring heavy artillery fire.

After the bombardment, Gen. Lee ordered several divisions forward to

attack the Union line, but they were easily repulsed. The rebels

suffered heavy casualties; the 28th none.

The Irish remained in and around the

vicinity of Manassas and Warrenton until October 23, when they moved

back toward the Rappahannock, finally crossing the river at Kelly's

Ford on November 7. The regiment established camp at Shackleford's

Farm, where they remained for nearly three weeks, many believing that

they would stay for the winter. But on November 26, they were ordered

out of camp to cross the Rapidan River at Germania Ford and begin what

would become known as the Mine Run campaign.

Moving forward with the 2nd Corps on the

November 29, the men of the 28th Massachusetts were deployed as

skirmishers, their left flank on the Plank Road near Robinson's Tavern.

Ordered to charge, the Irish drove the rebels they faced from their

rifle pits, capturing prisoners and scattering all opposition before

them. Col. Byrnes' men moved so quickly that reached the crest of a

hill well before the rest of the 2nd Corps did, losing nine men in the

process. There, they were halted to await the arrival of the other

regiments and prepare for the attack Gen. Meade planned to launch early

the next morning. But when he discovered that the Confederates had

strengthened their works and brought in reinforcements overnight, the

federal command called off the assault and his army withdrew across the

Rapidan to Brandy Station.

On December 5, the 28th Massachusetts

arrived at Stevensburg, Virginia, where it established winter quarters.

Except for an early February reconnaissance to the Rapidan, the

regiment would not see action again until the Union Army, under the

overall direction of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, began its relentless and

bloody Overland Campaign six months later.

On December 5, the 28th Massachusetts

arrived at Stevensburg, Virginia, where it established winter quarters.

Except for an early February reconnaissance to the Rapidan, the

regiment would not see action again until the Union Army, under the

overall direction of Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, began its relentless and

bloody Overland Campaign six months later.

By the end of 1863, year the Union high

command realized that the enlistments of many veteran regiments would

expire by the middle of the following year. This would have dire

consequences for the federal war effort, so Congress was compelled to

act. It first authorized existing units to continue as "veteran

volunteer regiments" if they were able to re-enlist two-thirds of their

men. Units falling short of these numbers would be disbanded when their

terms ran out.

To induce soldiers to re-enlist with their regiments, the federal

government offered them 30-day furloughs and cash payments of $402. The

Commonwealth of Massachusetts, meanwhile, offered $325 over and above

the federal incentive to all of veterans who re-enlisted by January 1,

1864. Whether it was their patriotism, a sense of

imminent victory, or the prospect of receiving what was then a huge sum

of money, 157 veterans who had signed on with the 28th Massachusetts in

late 1861 and early 1862 re-enlisted.

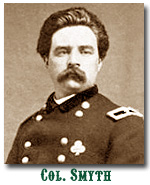

An

additional incentive may have been the welcome news that Col. Thomas A.

Smyth, formerly of the 1st Delaware Infantry, had been selected to

command the Irish Brigade. Smyth was a fellow Irish immigrant who had

won plaudits as a brigade commander in the 2nd Corps for "bravery

almost amounting to rashness." Although he was a strict disciplinarian,

he was ever attentive to the needs of his men, and never stayed in the

rear for long when they became engaged with the enemy.

An

additional incentive may have been the welcome news that Col. Thomas A.

Smyth, formerly of the 1st Delaware Infantry, had been selected to

command the Irish Brigade. Smyth was a fellow Irish immigrant who had

won plaudits as a brigade commander in the 2nd Corps for "bravery

almost amounting to rashness." Although he was a strict disciplinarian,

he was ever attentive to the needs of his men, and never stayed in the

rear for long when they became engaged with the enemy.

Continued

>